Foreword

In an increasingly competitive global environment, ensuring that the UK remains a leading destination for life sciences innovation has never been more critical – or more challenging. The UK life sciences industry faced a turbulent year in 2025, with rapidly escalating VPAG (voluntary scheme for branded medicines pricing, access and growth) rates signalling the growing divide between the needs of the health service and the level of sales of branded medicines permitted under the scheme. The UK industry has also faced geopolitical pressure, including the possibility of tariffs and the implementation of ‘most-favoured-nation’ pricing in the US, which aims to ensure that US payers do not pay more than those in other developed countries.

In July last year, the government set out its ambition to make the UK the best place in the world to research, develop and manufacture medicines in the Life Sciences Sector Plan – an aspiration shared by the ABPI and our members. However, the VPAG expedited review failed to reach an acceptable conclusion for the industry.

In December, the UK and the US announced an agreement to take forward a number of policy reforms, including an increase in the NICE baseline cost-effectiveness threshold, a ceiling to the VPAG payment rate to protect industry from future surges in rate, and long-term spending commitments to bring the UK closer to a more internationally competitive position.

The deal is an important step towards ensuring patients can access innovative medicines needed to improve wider NHS health outcomes. It should also put the UK in a stronger position to attract and retain global life science investment and advanced medicinal research. It is now vital the details of this agreement are finalised and communicated as soon as possible for us to be able to work together to deliver these reforms.

These commitments begin to address industry concerns on NHS access to medicines, and the UK’s record-high and volatile payment rate. There remain a great many details to work out and further technical improvements to make, but with this strong and positive progress, I look forward to working with the government to ensure this plan delivers for the NHS, patients and UK industry.

The purpose of this report is twofold: to provide evidence of the decline that was accelerating as a result of policy up to this point; and set a baseline against which the success of the reforms can be measured – for companies’ operations, investment and medicines launches, ultimately benefitting NHS patients and driving economic growth.

However, as the findings in this report make clear, the opportunity created by this agreement remains fragile. The Medicines Impacts and Investment Survey (MIIS) was carried out at one of the most challenging points the sector has faced in recent years, and it records real-world consequences of past policy choices: delayed and cancelled launches, disinvestment in UK R&D and manufacturing, and growing uncertainty over future headcount and capital allocation. It also highlights the ongoing risks posed by external pressures, such as the US’s most-favoured-nation pricing, which means that UK decisions on net prices and cost-effectiveness thresholds now carry broader international implications.

The challenge now is to consolidate this progress and avoid repeating past cycles of volatility and uncertainty. That requires credible implementation of the reforms, explicit signalling on future decisions across the VPAG, pricing policy and adoption of medicines, and a sustained focus on competitiveness and patient access and uptake. The ABPI is committed to working with government, the NHS and patients so that this agreement marks the start of a lasting reset for UK life sciences.

|

Richard Torbett, |

Executive summary

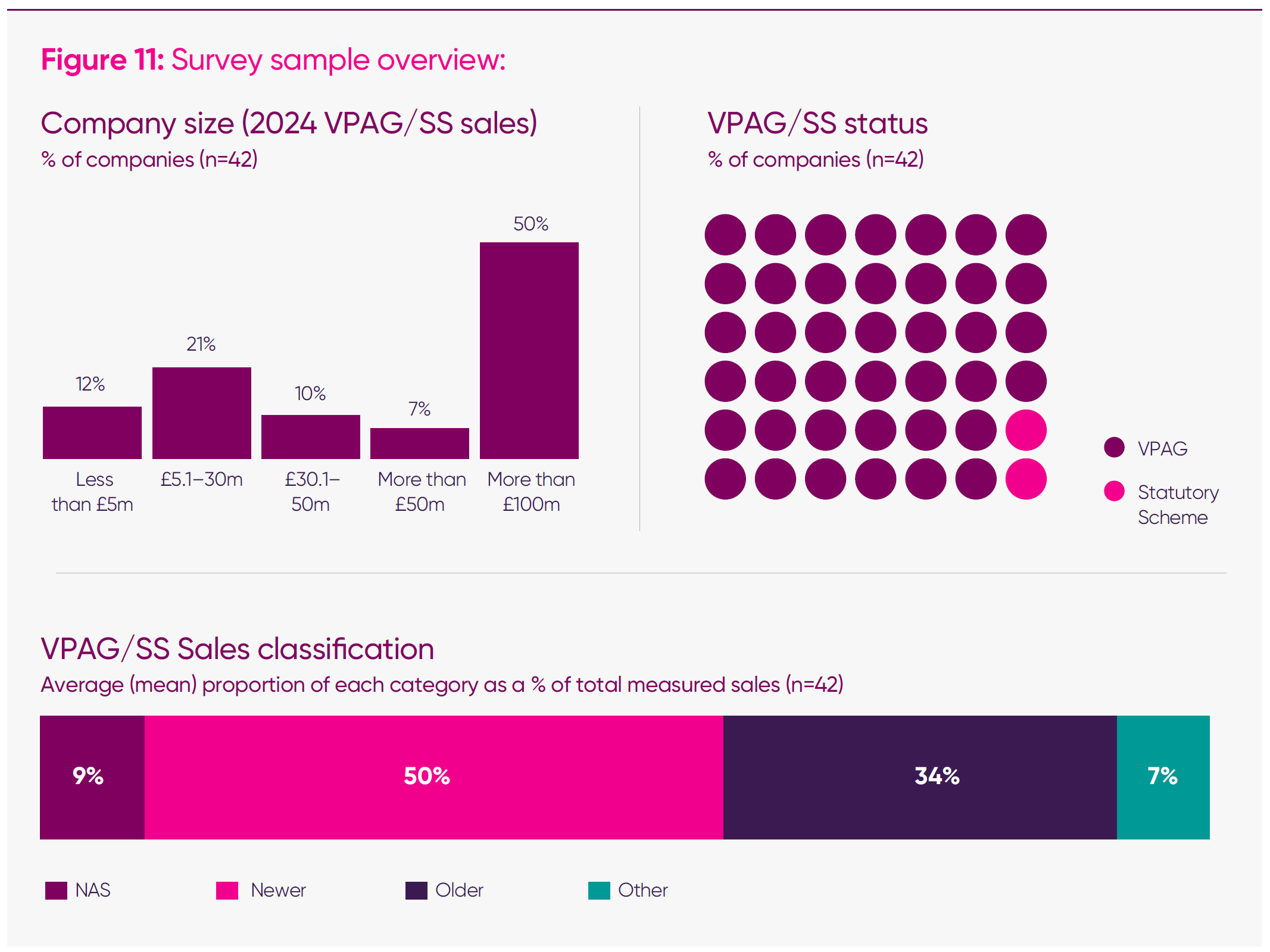

In September 2025, the ABPI conducted the MIIS, calling for input from all UK-based branded medicine manufacturers.

Earlier in 2025, the ABPI’s Competitiveness Framework, Creating the Conditions for Investment and Growth 1, benchmarked the UK against peer countries across the full range of factors that drive life sciences investment. While it confirmed the UK’s fundamental strengths in science, talent and infrastructure, it also showed that the UK’s most significant weaknesses lie in its commercial environment – in particular, levels of investment in medicines, patient access and the predictability of clawback rates. Against that backdrop, this report focuses on how those commercial pressures are already influencing companies’ investment decisions and launch strategies in real time.

The survey took place during a period of acute uncertainty for the sector. The expedited VPAG review had failed to reach an agreement between government and industry. In parallel, the UK and US governments were negotiating the implementation of the Economic Prosperity Deal, and global pharmaceutical companies were calibrating their responses to the US administration’s most-favoured-nation pricing policies, which reference net prices paid in countries like the UK to lower prices for US patients. This uncertainty was clear in companies’ responses.

The results reveal clear and quantifiable shifts in company sentiment and behaviour since January 2024. In this latest survey, across 42 companies, responses show falling confidence, active disinvestment, and declining UK launch prioritisation following sustained – and strengthening – headwinds in the UK commercial environment.

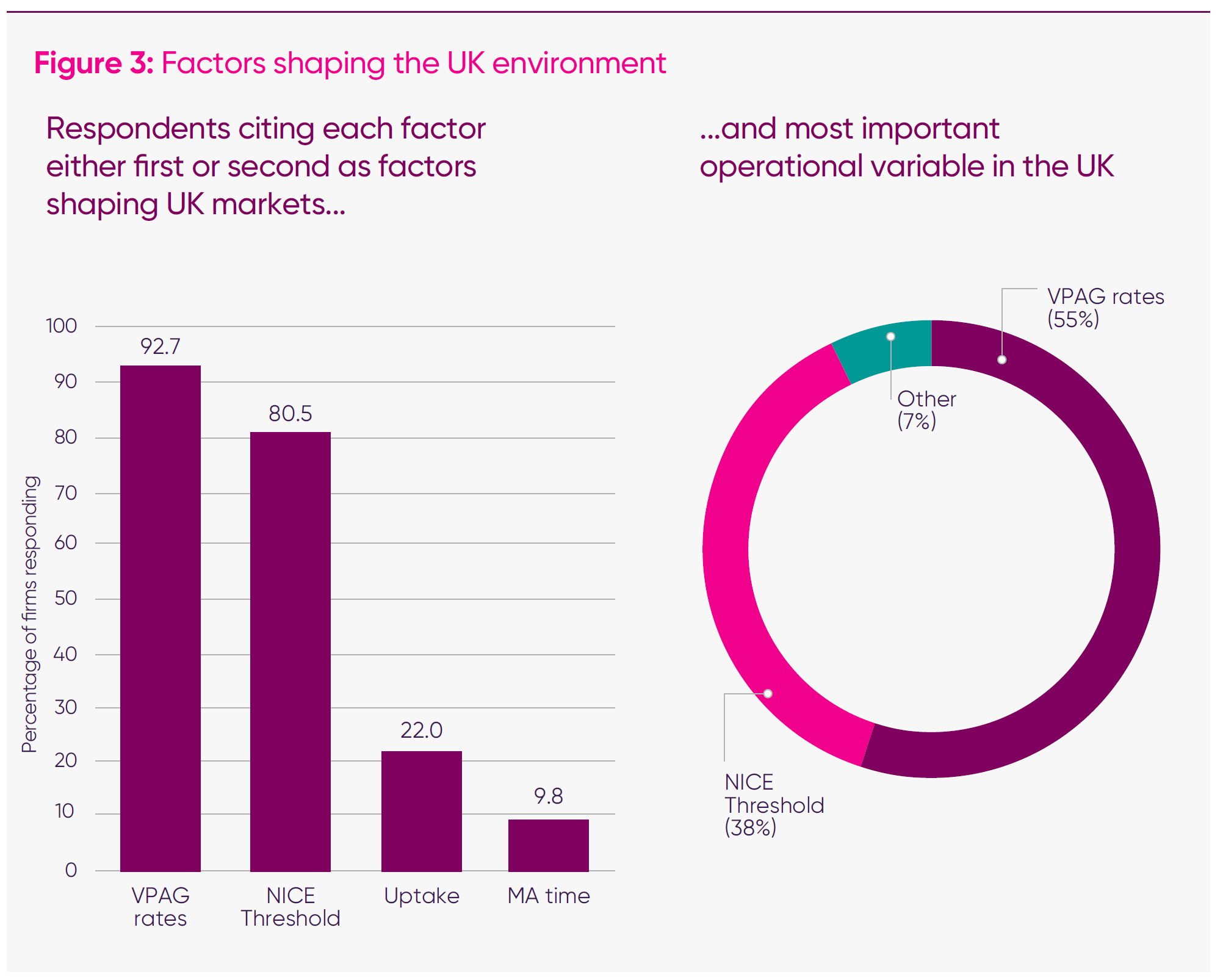

1. Respondents are overwhelmingly clear that NICE thresholds and sustained high VPAG payment rates have acted as a dual drag on the UK’s international competitiveness in attracting value-adding activity.

- Nine in 10 (91 per cent) of responding companies cited VPAG payment rates and NICE appraisal thresholds as the top two factors shaping companies’ operations in the UK.

- Well over half (55 per cent) identify the VPAG as the single most important reform to improve the UK’s competitiveness for life sciences companies, promoting launches, investment, and increased activity.

- Two-fifths (38 per cent) of companies identified NICE thresholds as the most critical reform needed to improve the UK’s competitiveness.

2. The UK has been declining as a global launch market; launches were increasingly delayed or cancelled, potentially impacting patients’ access and outcomes.

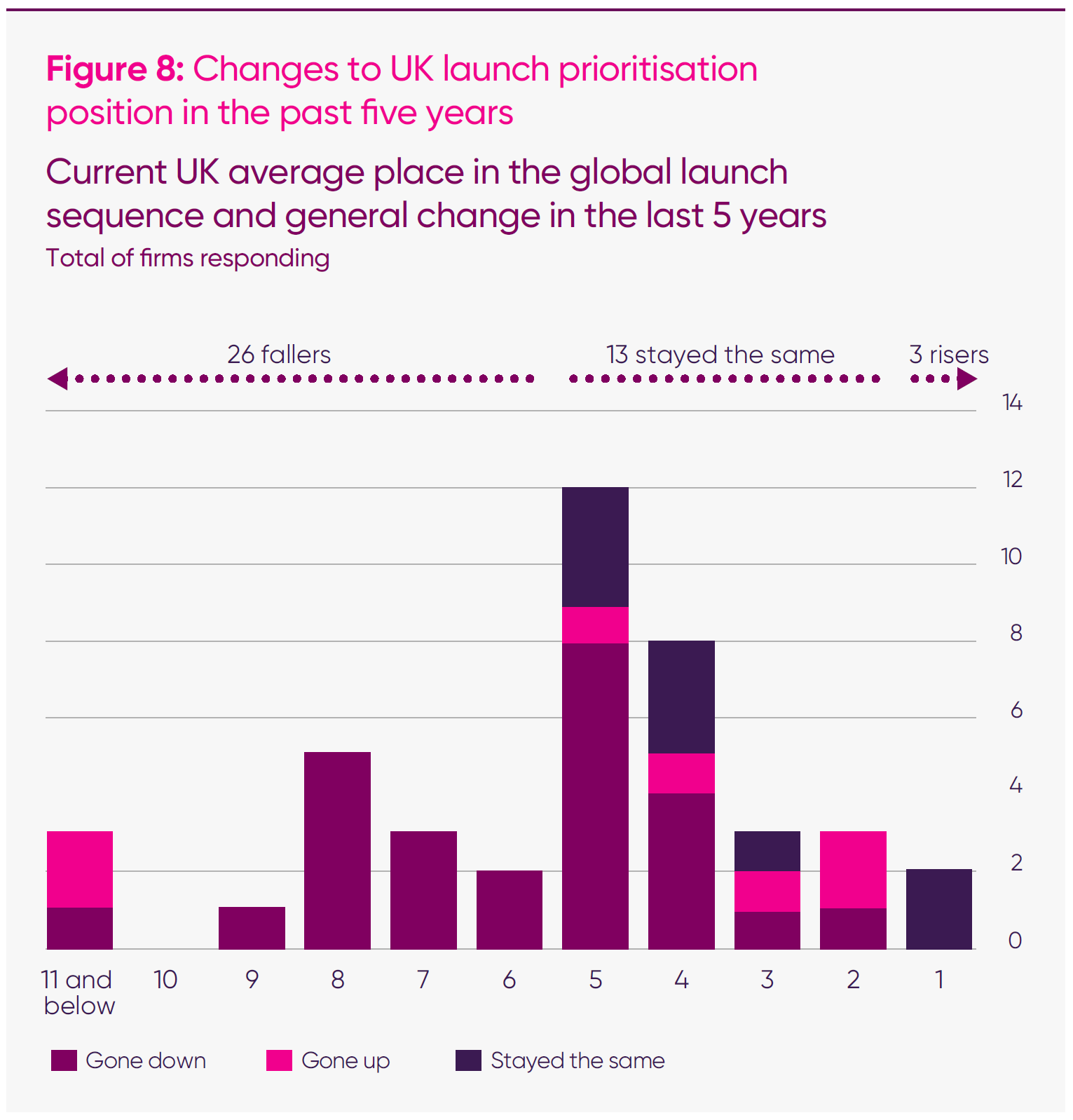

- Two in three (26 out of 42) of responding firms reported that the UK had fallen in global medicine launch sequences over the past five years.

- Well over two in three (68 per cent) of companies confirmed that current VPAG rates were directly impacting their launch sequencing.

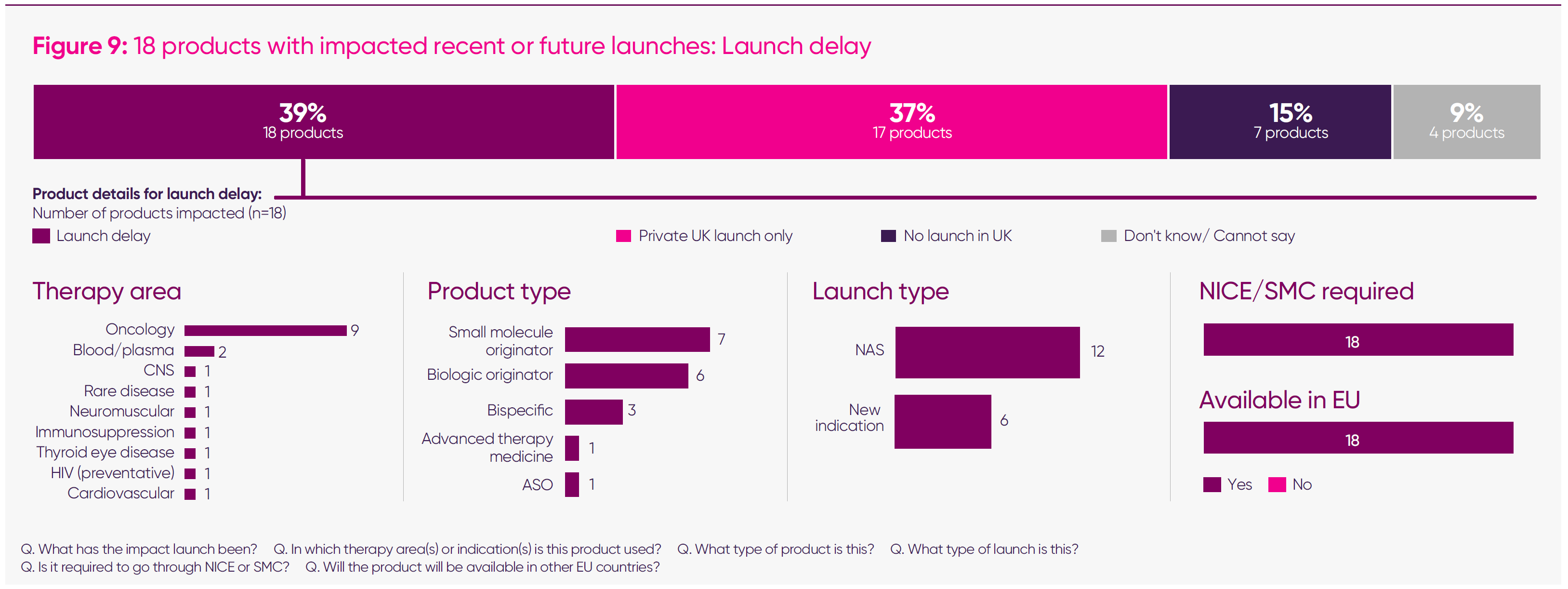

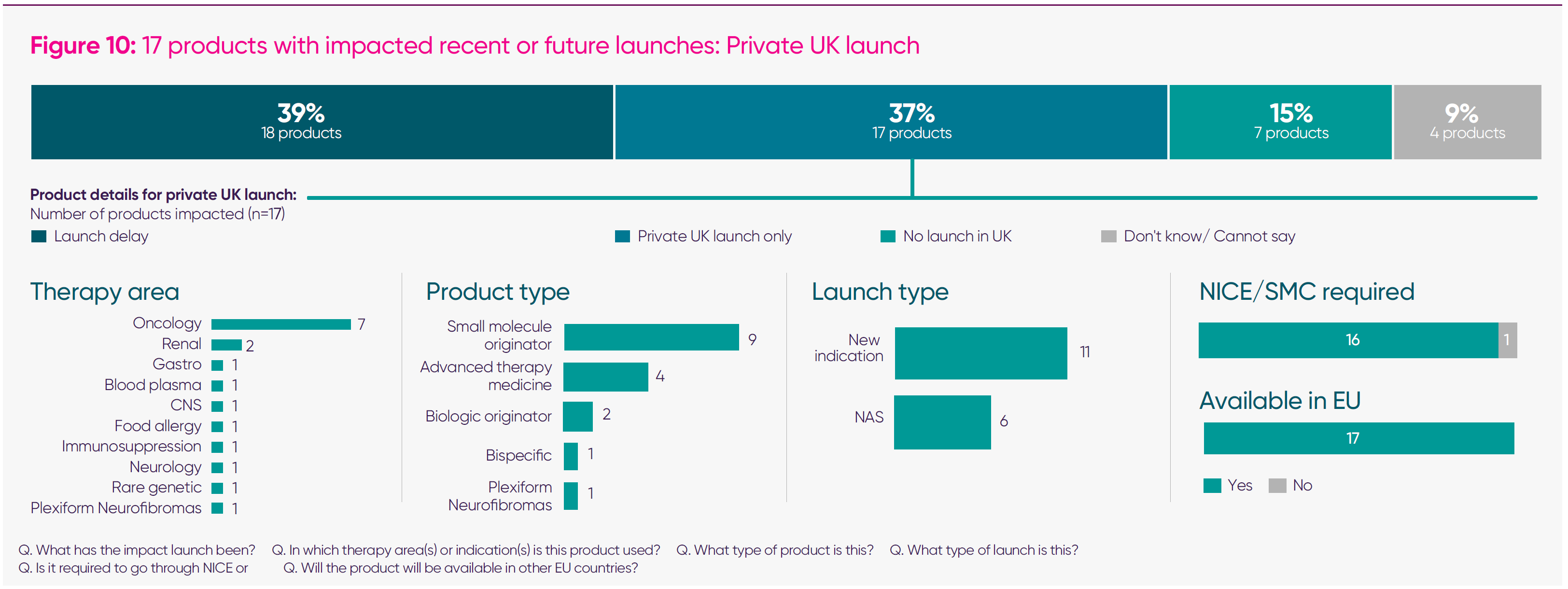

- Forty-six medicines were reported by companies as having their launch impacted since January 2024: 18 list a launch delay; 17 were launched for private patient use only; and seven had no UK launch (for the remaining four medicines, the launch impact was still uncertain). Of these medicines, 96 per cent required NICE/Scottish Medicines Consortium authorisation,2 and 100 per cent are, or will be, available in other EU countries.

- When compared with the total pipeline for the companies responding to the survey (which we assessed using medicines going through the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use), we found that 20 per cent of the expected pipeline suffered a negative impact for 2024–25; 10 per cent will not be available to NHS patients.

- The medicines most affected by delayed or constrained UK launches are predominantly new active substances and newer indications, concentrated across oncology – with medicines for lung, ovarian, prostate, and breast cancer – as well as other medicines in rare diseases, cardiovascular, and central nervous system.

3. Workforce reductions are now visible and accelerating

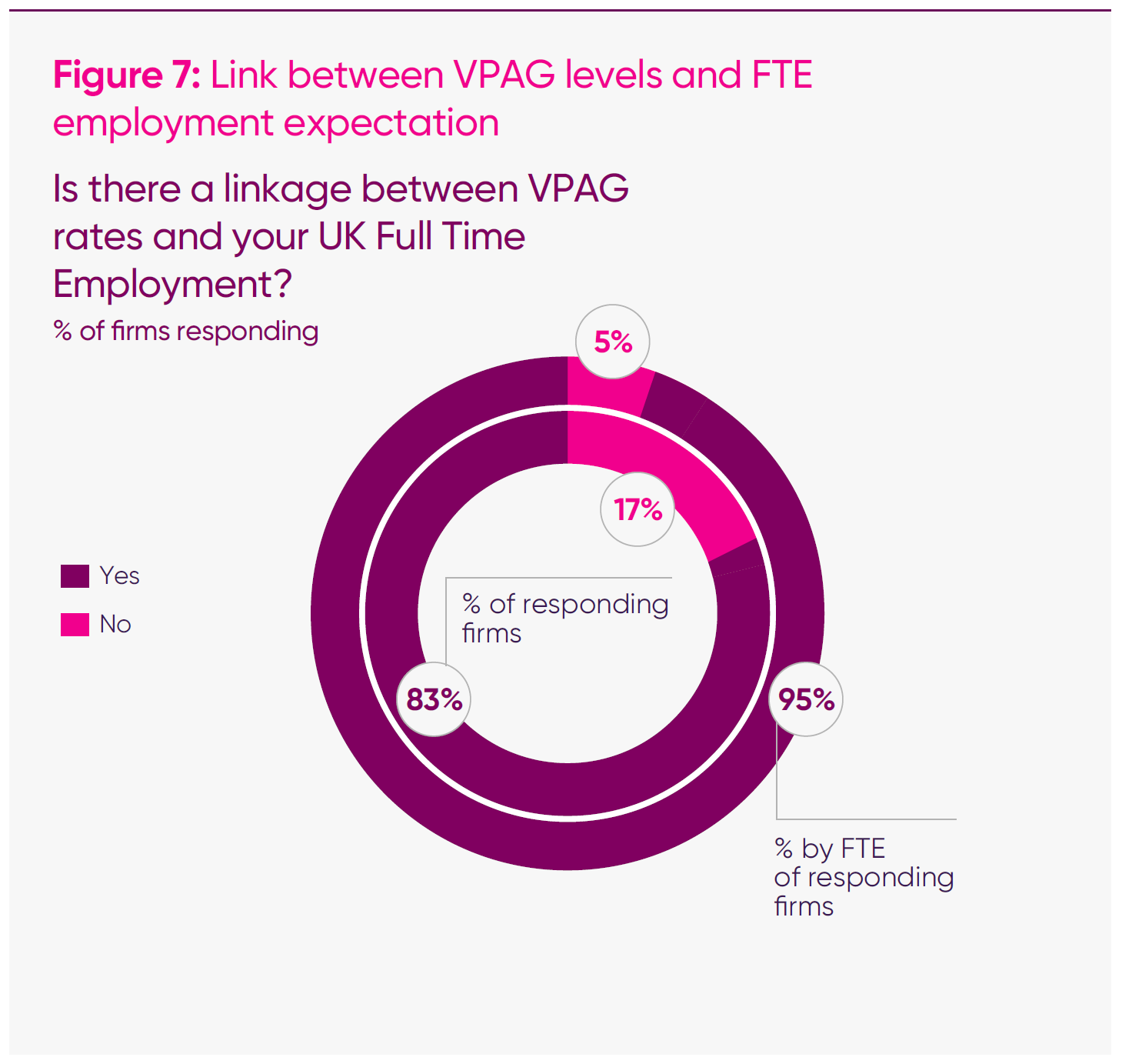

- Well over four-fifths (83 per cent) of responding companies said that current VPAG payment rates were directly influencing headcount decisions. This is an increase from the first half of 2025, when 61 per cent of responding companies said they were a factor.

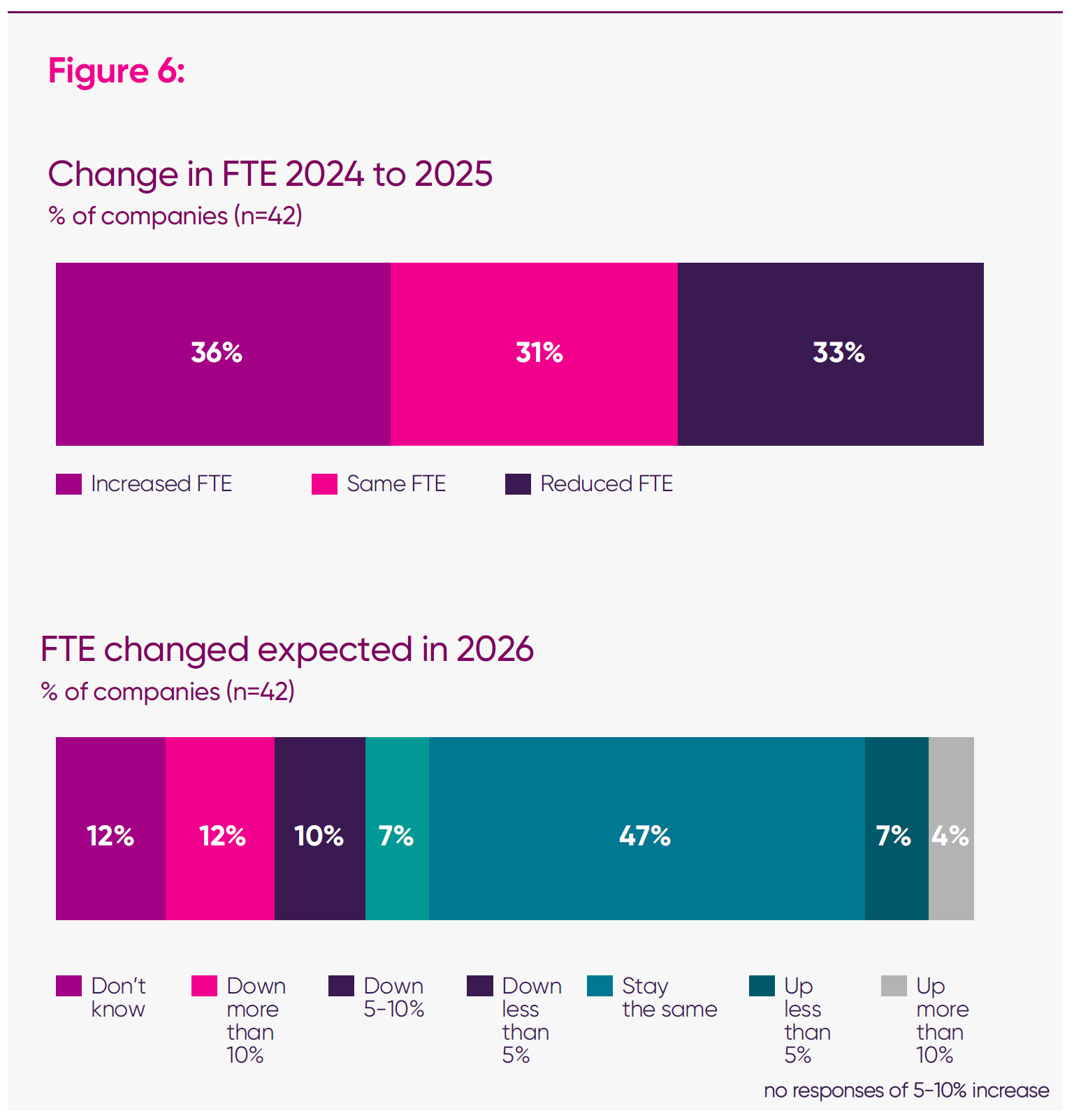

- When previously surveyed in April 2025, three in 10 (29 per cent) of companies anticipated growth, one in 10 (8 per cent) anticipated reductions, and a final three in 10 (29 per cent) answered ‘don’t know’. In this survey, uncertainty crystallised into negative expectations: looking ahead, 29 per cent anticipate reducing full-time equivalent (FTE) in 2026, with only 12 per cent expecting growth.3

- This risk is even more pronounced among medium and larger firms, which together account for 98 per cent of 2025 FTE (around 30,000) across the survey.4

4. Investment intentions have shifted from growth to containment

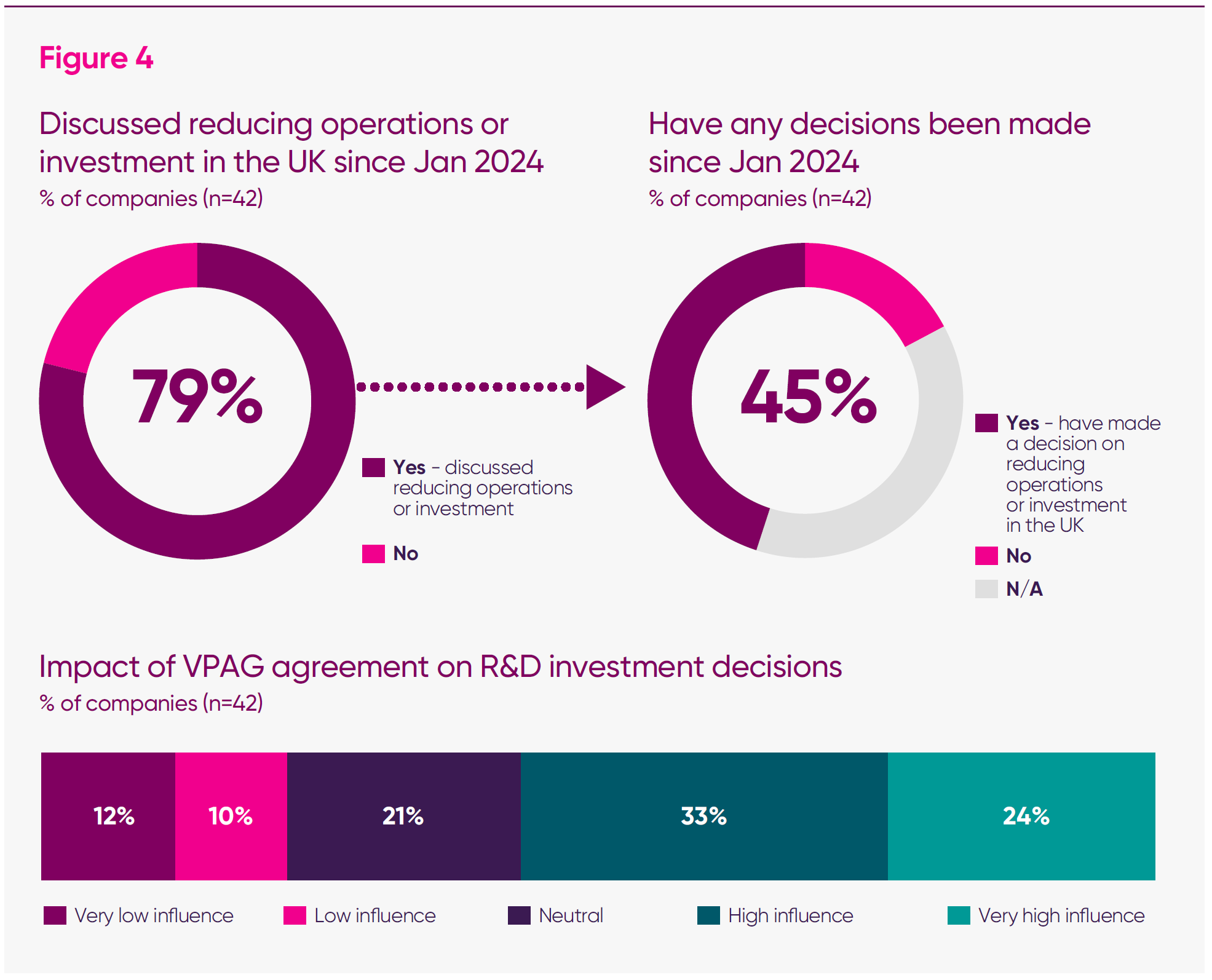

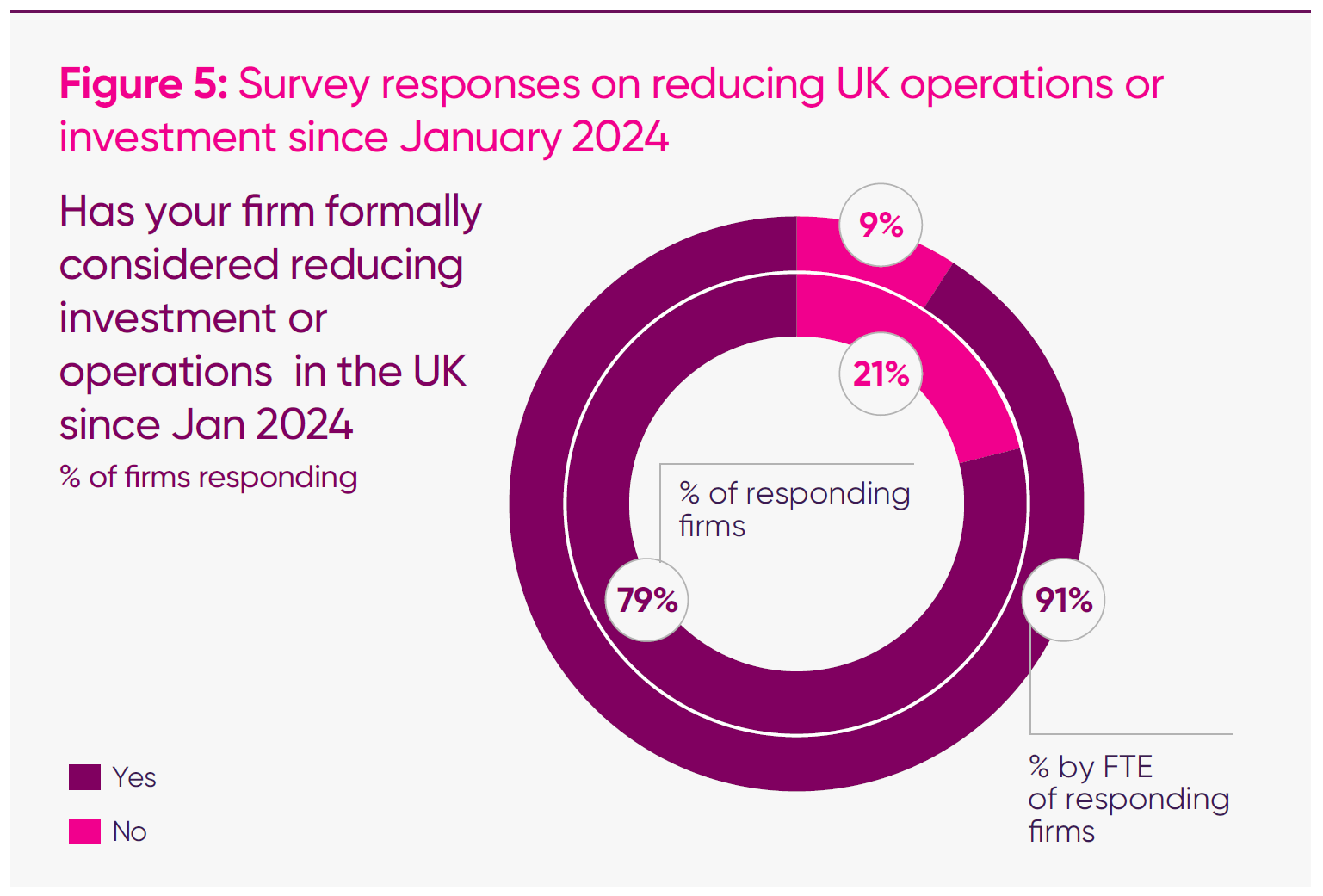

- Four in five (79 per cent) of responding firms said that their firms had considered operational or investment reductions in the UK since January 2024.

- When weighted for FTE, 91 per cent of companies have considered retrenchment from the UK since January 2024.

- Among those firms that have discussed reductions, around three-fifths report having already decided to cut, defer or cancel UK investments.

- In responses on ‘investments most at risk’, clinical trials and wider R&D programmes are most frequently cited, followed by UK commercial expansion and corporate roles; around two-thirds of firms answering this question single out clinical trials or closely related clinical research as the UK investment they expect to reduce or divert to other countries.

5. Companies are continuing to report VPAG rates as a factor leading to branded medicines withdrawing from the UK market

- Twenty-four medicines have faced viability challenges – either having already been withdrawn or potentially facing withdrawal.

- The VPAG was cited as a cause of these challenges in two-thirds (67 per cent) of medicines; VPAG was identified as a factor in all nine medicines that have actually withdrawn from the market. Companies explain in their responses that, where margins are already thin, having to pay back up to 35 per cent of their sales can mean making a loss on every sale.

- While the UK has a broadly well-functioning medicines supply ecosystem, these dynamics can impact therapy areas that are already prone to supply disruption – for example, ADHD and women’s health. Companies have reported that they have had to request exceptional pricing treatment for medicines in these categories; there is evidence that the UK could be at greater risk of deprioritisation or discontinuation where supply issues occur.

6. Confidence can be rebuilt – but predictability and competitiveness are key

- Although sentiment captured in the survey was profoundly negative, most responding companies recognise that the UK retains significant underlying strengths and believe that recovery is possible if the agreed reforms are implemented in a way that restores international competitiveness in the commercial environment.

- The ABPI’s previous report, ‘Opportunity Unlocked’, modelled the scale of that prize, estimating that the benefits of returning the UK to a position of international competitiveness could recover up to £11 billion of R&D over 2024–2033, generating £93 billion in GDP.5

- When explaining the reforms that would have the most significant positive impact on their companies, respondents consistently highlight the interdependence of the levers – VPAG clawback rates, NICE health technology assessment (HTA) thresholds/methods and the speed and consistency of uptake – as the main determinants of UK attractiveness, and the critical enablers of life sciences success.

The policy context: the widening gap between ambition and reality

By the time the MIIS was conducted, it had become clear that the commercial conditions required to realise this vision had been moving in the opposite direction. Despite a sustained policy emphasis on life sciences as a national growth priority, the environment underpinning investment in medicines had diverged sharply from the ambitions it was intended to support. The subsequent Economic Prosperity Deal and associated reforms were agreed against this backdrop.

Survey responses consistently refer to two underlying structural pressures that sit at the heart of this challenge.

1: What strength in basic science can and cannot do:

- The UK’s strong basic science base is a major asset: it fuels discovery, attracts talent and generates the ideas that start the medicines pipeline. But basic science alone does not drive investment, development or launches.

- As the ABPI’s Competitiveness Framework shows, companies base decisions on a wider set of factors, including clinical trial performance, regulatory clarity, commercial sustainability, fiscal incentives and the overall ease of operating in a given market.6

- This framework identified the commercial environment as the UK’s weakest area. The scale and unpredictability of recent VPAG rates have made the UK a significant outlier in many global boardrooms. Even as recent reforms aim to stabilise the regime, the view of the UK as a ‘contagion risk’ could take time to moderate.

- This means strong science cannot compensate for weaknesses elsewhere. If the UK becomes less attractive for development or launch, activity shifts to markets where the entire environment is aligned. Over time, that reduces partnerships and translational opportunities, weakening the very ecosystem that supports basic research.

By the time the MIIS was conducted, it had become clear that the commercial conditions required to realise this vision had been moving in the opposite direction. Despite a sustained policy emphasis on life sciences as a national growth priority, the environment underpinning investment in medicines had diverged sharply from the ambitions it was intended to support. The subsequent Economic Prosperity Deal and associated reforms were agreed against this backdrop.

Survey responses consistently refer to two underlying structural pressures that sit at the heart of this challenge.

First, there is long-term underinvestment: a structural squeeze on branded medicine spending.

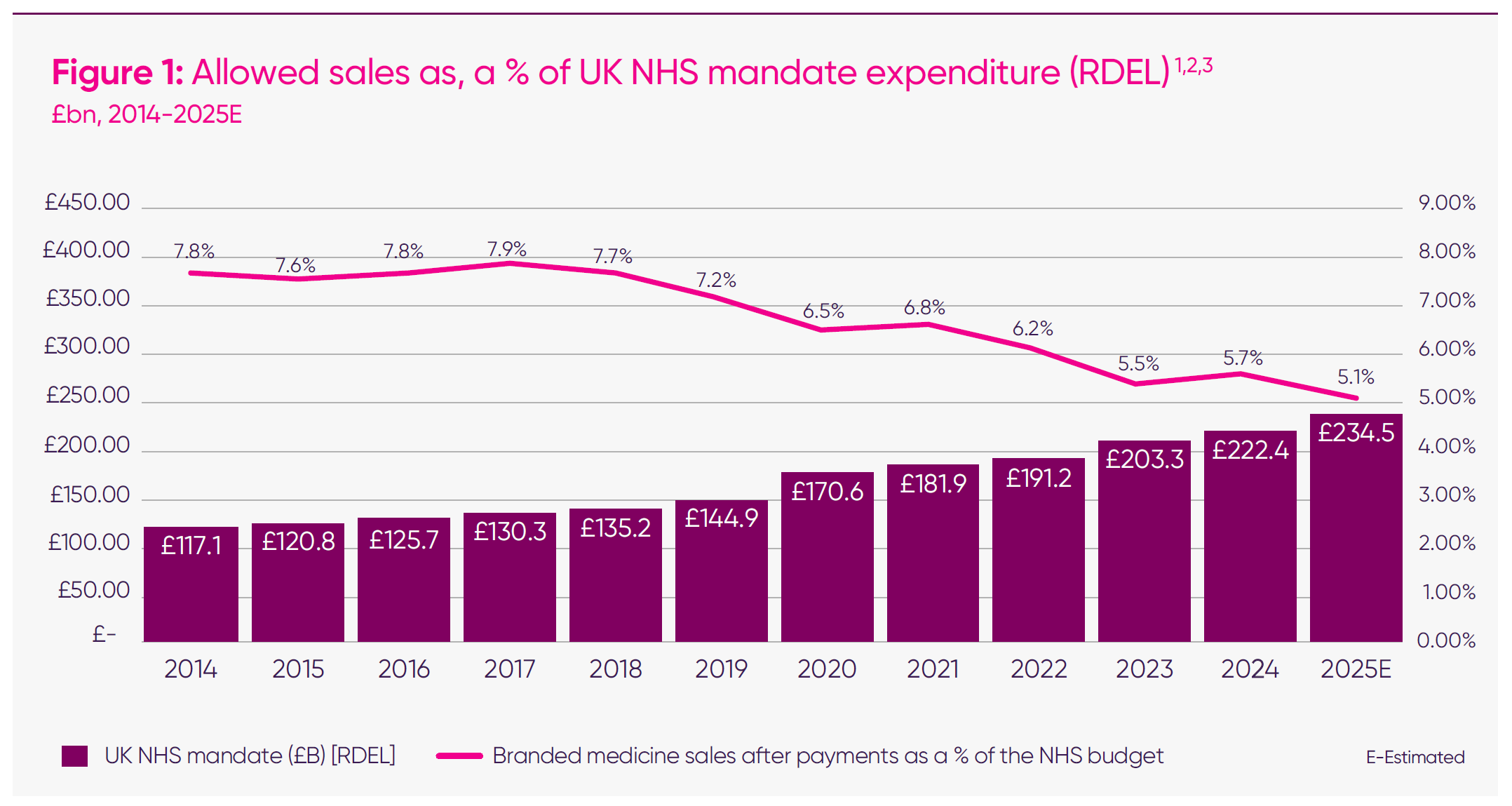

The UK has allowed a substantial and persistent divergence between growth in NHS spending and demand for branded medicines. Between 2014 and 2025, the NHS budget has risen by around 43 per cent in real terms, while the level of spending permitted under successive voluntary pricing schemes for branded medicines has fallen by roughly 10 per cent.7

As highlighted in the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science’s ‘Drug Expenditure Dynamics 2000–2022’ report, the UK’s ratio of medicines spend to total healthcare spend has remained below 10 per cent – well behind comparator countries such as Germany and France, which invest closer to 13–14 per cent.8 In practical terms, this means the UK is systematically budgeting less for medicines and vaccines than its peers. This structural divergence has now become entrenched. It has persisted through three consecutive agreements, meaning that every year the NHS grows, the effective share available for investment in new medicines declines. As a result, allowed sales as a proportion of the total NHS budget have dropped from around 7.8 per cent in 2018 to just over five per cent by 2025, even though the overall NHS mandate has grown sharply in cash and real terms.9

This is what makes the government’s agreement to increase its share of health spending on all medicines – branded and generic – significant, alongside both long- and short-term commitments to the percentage of GDP allocated to newer medicines. Together with capping VPAG payments for newer medicines at 15 per cent, this rebalancing should help address some of the pressure that has built up on the sector over a decade as the sole holder of market risk.

UK allowed spend on branded medicines has fallen by over 9 per cent, while the NHS’s budget has grown by 44 per cent since 2014.10

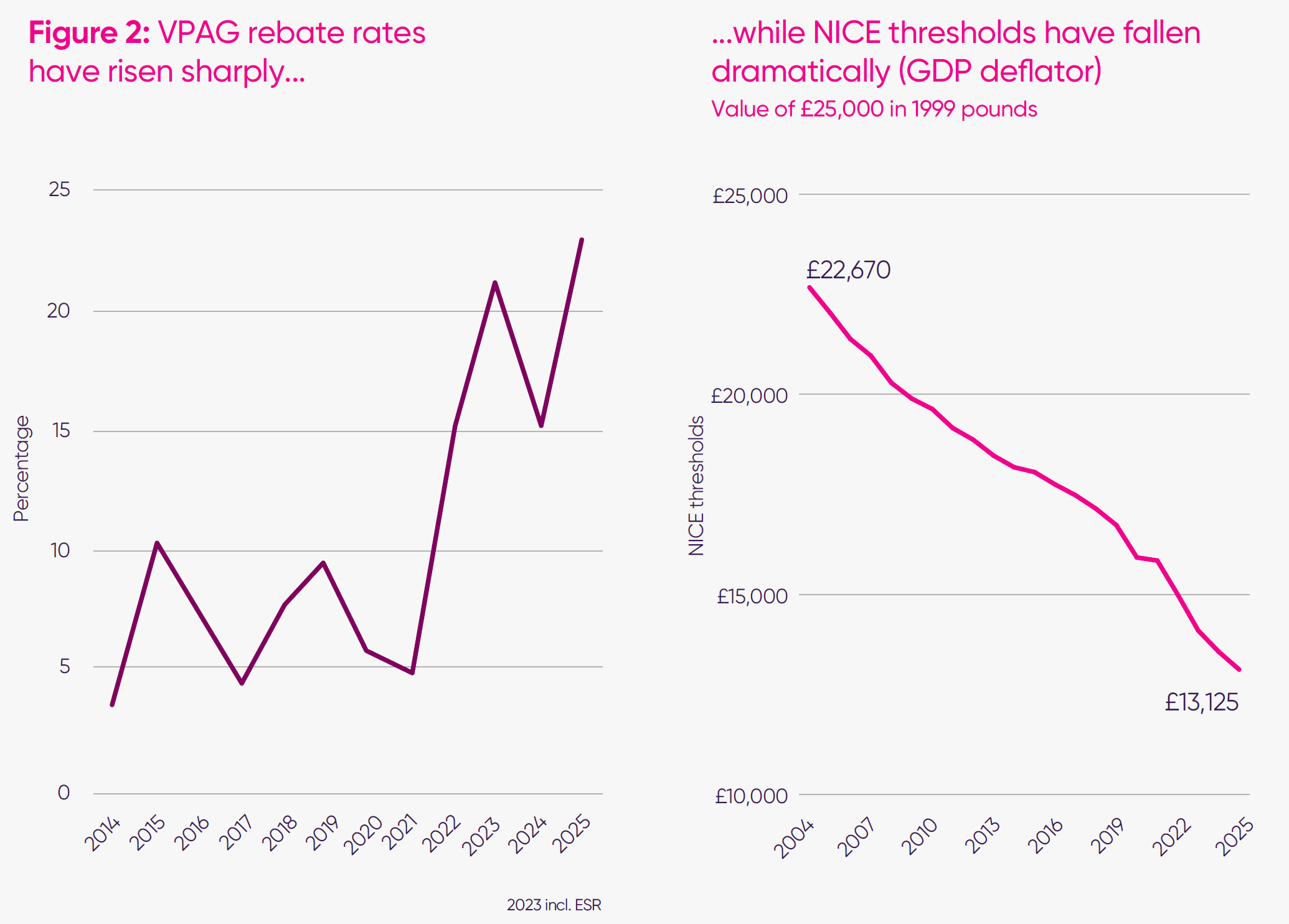

As survey respondents explained, the VPAG design caused issues not only because of the magnitude of the rates but also because of their volatility. For newer medicines, the 2025 rate increase of around 50 per cent (7.6 percentage points) was published with just days remaining of the working year – too late for companies to adjust their operating plans. This forces companies to make in-year reductions, often involving FTE reductions or pausing investments. For smaller and mid-sized firms, respondents described limited ability to absorb sudden changes in the VPAG, with some indicating that further late-stage investment or expansion of their UK footprint would be difficult to sustain in the current environment. Larger multinationals can absorb short-term losses but cite volatility as a significant deterrent to incremental investment. This is in addition to payments for older medicines, which can be as high as 35 per cent for some products. Companies responding to the MIIS survey described the UK as a “high-risk, low predictability” market, where annual VPAG payment rate announcements have become material events for global planning.

Long-term erosion in value recognition

While the VPAG has constrained the UK’s competitiveness relative to international peers in overall spend on medicines, an equally significant pressure has come from the valuation framework used to assess new medicines.

Before the government agreed to increase the threshold, NICE’s baseline cost-effectiveness threshold, which is used to determine value for money, had remained unchanged for more than 20 years. Over time, this has meant that the real-terms value the NHS places on health gain has steadily fallen, even as scientific advances have accelerated.

International comparisons highlight the scale of this erosion. At £25,000 per quality adjusted life year (QALY) (midpoint of the current threshold range), the UK’s threshold sits well below the international average of £33,400 across 36 comparable countries, placing it in the bottom third globally.12

When benchmarked against GDP per capita, the gap is even more striking: the UK’s threshold is more than 30 per cent below GDP per capita, indicating a more conservative willingness to pay for health improvement than is typical among high-income countries.13

This positioning has reinforced a perception that the UK is not paying its fair share relative to national wealth, and that its valuation framework has not kept pace with the global environment in which investment and launch decisions are made. The recent agreement to increase the threshold is an important step to address this.

Survey respondent:

“The NICE HTA threshold hasn’t changed since 1999 and makes it increasingly difficult to secure a business case for UK launches of new medicines, as it’s more difficult to achieve an economically viable price, combined with paying NICE fees and then poor uptake once you get recommended. If the NICE threshold were fairer and adjusted in line with inflation and uptake post-recommendation was better, that would make the UK more attractive. Even if clawback rates reduced, the NICE threshold is still low and there is no uptake after recommendation, which makes the business case for the UK much harder.”

Drag anchors on the UK’s competitiveness

Together, these two key factors, alongside persistent wider challenges in the medicines access environment, including requirements for commercial flexibilities, and widespread local variation in medicines uptake, have operated as a set of structural drag anchors on the UK’s competitiveness in attracting medicines and the R&D that supports them.

Survey respondent:

“The VPAG significantly impacts our ability to invest in the UK today and in the future. NICE HTA thresholds coupled with high VPAG rates impact our ability to launch innovative medicines. In combination with the low net price and slow uptake of UK medicines, we are now experiencing the UK drop in the global priority list for both launch sequences and stock availability.”

Ben Lucas, MSD15:

“There is a chronic underinvestment in medicines. The investment in medicines – the budget spent on innovative medicines – has not been raised at the same rate that other spend in the NHS has over time. The UK has dropped down the league tables in terms of spend on medicines, either as a proportion of GDP or as a proportion of the overall health spend.”

2: Why disinvestment matters

- This report and the MIIS refer to the UK’s ‘competitiveness’ and ‘attractiveness’ for investment. But it is important to be clear that these are a means to an end, in themselves. Reduced commitments to the UK flow through to ‘the frontline’ in several ways.

- Withdrawn launches and private-only market entry inhibit patients’ access to innovative and life-saving medicines. Because NICE judges whether a medicine is clinically effective and considered to provide value for money and the VPAG informs the net price a supplier will ultimately be paid, reduced commercial attractiveness directly shapes the quality and timeliness of patient care.

- Disinvestment also affects the UK’s role in global R&D. Companies that deprioritise the UK as a launch market often place fewer clinical trials and less development activity here, because clinical trials require the gold standard as a comparator and this cannot happen in markets where launches have been pulled or deprioritised; companies also have an ethical obligation to run clinical trials in countries where they are likely to be able to launch a medicine.

- In turn, this reduces opportunities for patients to join trials, limits clinician involvement in cutting-edge research and weakens the broader ecosystem that sustains innovation.

This divergence is no longer theoretical. It is visible in company-level decisions, and in the scale of investment paused or withdrawn. Earlier this year, MSD announced the cancellation of its planned expansion of early-stage discovery research in London – an investment that had been several years in development.16

A further prominent example of revised investment intentions can be seen in AstraZeneca’s pause of a £200 million development in Cambridge, following the cancellation of major manufacturing and research expansions announced in March 2024.17

Unfortunately, these are far from the only examples of significant disinvestments that have occurred in the last decade or so – ABPI analysis has found more than 10 other examples since 2015.

As demonstrated in the ABPI’s Competitiveness Framework, since 2018, UK Pharmaceutical R&D investment has underperformed against global trends, with a significant slowdown starting in 2020, when UK growth fell to 1.9% per year, behind the global average of 6.6% annual growth. Pharmaceutical industry investment in R&D actually fell in 2023 by nearly £100 million.

Life sciences foreign direct investment into the UK was around 58% lower in 2023 (£795 million) than in 2017 (£1,893 million). The UK’s ranking among comparator countries fell from a high of 2nd in 2017 to 7th in 2023.

Together, these trends emphasise a growing mismatch between the UK’s scientific strengths and the incentives needed to translate them into investment.

This pattern was examined in depth during the Science, Innovation and Technology Committee’s recent inquiry into life sciences investment. Evidence from AstraZeneca, MSD and the ABPI painted a consistent picture: NICE baseline thresholds that have remained unchanged since 1999, sustained high VPAG payment rates, and a long-term fall in the share of NHS spending devoted to medicines are all constraining the UK’s ability to support competitive launch, adoption and scale-up of new treatments.18 Those conclusions on underspend and the need for a predictable commercial framework clearly underpinned the later US deal and reforms.

During the same committee hearing, UK science minister Lord Patrick Vallance noted that medicines’ share of NHS expenditure has fallen from around 12 per cent in 2015 to roughly 9 per cent today, and that this trend “has to be reversed” to sustain UK competitiveness. Similarly, life science minister, Zubir Ahmed MP, emphasised that the UK “wants to see a direction of travel where we spend more money on novel, disease-modifying medicines,” and highlighted the need for a more predictable, internationally credible commercial framework.19

Even before this agreement, there was substantial acknowledgment across government and industry on the need for the UK government to spend more on medicines if they are to be a routine part of public healthcare. This report demonstrates why the UK’s new commitments to higher spending and a more predictable framework must be delivered in practice for the benefit of UK patients, the NHS and the economy.

A clearer picture of how confidence is shifting over time

The 2025 ABPI MIIS provides the clearest view yet of how life sciences companies have been adjusting their launch and investment decisions in response to the UK environment. The MIIS has been set up to track impacts longitudinally rather than relying on one-off snapshots, with the objective of providing a truer picture of how confidence evolves as the policy and market landscapes shift. It will be vital to keep tracking this as we understand the impact of these policy reforms and their interaction with the US’s most-favoured-nation pricing policies going forward.

Detailed survey insights

1. Rising VPAG rates are associated with lower investment and R&D expectations in the UK

‘Opportunity Unlocked’ set out the relationship between the sector’s revenue and investment in the UK. Pharmaceutical R&D is mainly financed from operating cash flow, so reductions in net revenue translate quickly into smaller discretionary R&D budgets and tighter hiring envelopes. Under the VPAG, payments function as a levy on sales (not profits), lowering realised UK net prices and creating year-to-year cash outflows that compress liquidity available for pipeline work, trials and UK headcount. As companies noted in their responses, rapidly rising rebate rates at the time of the survey also necessitated immediate headcount reductions, as they have limited levers for balancing their pressures in-year.

Responses in the MIIS, which underpin this report, demonstrate a clearer and stronger relationship between VPAG payment rate levels and companies’ expectations for investment and R&D activity in the UK, even compared with the first half of 2025.

Across the dataset, firms identified the VPAG as a key factor shaping planning and their future footprint. The evidence indicates that, during the period when VPAG payments were rising, confidence in maintaining or expanding UK operations was weakening, and expectations for both investment and R&D were declining. These dynamics help explain why stabilising the VPAG and reducing rates for newer medicines became a component of the subsequent Economic Prosperity Deal and associated reforms.

Survey respondent:

“There are multiple factors that impact R&D investment but the most significant is whether the UK is competitive. Global competitiveness in where we conduct our clinical trials requires that we implement our studies in commercially relevant markets that offer patients a modern standard of care. A rebate rate that is higher than our comparator countries makes the UK less competitive and any levels above industry forecasts exacerbate this much further.”

These findings map directly onto the ABPI Competitiveness Framework

In recent years, VPAG volatility has served as a clear ‘contagion risk’, while long-standing NICE valuation parameters have acted as a ‘critical differentiator’ shaping whether global boards view the UK as a commercially viable launch market. Together, these pressures weaken the UK’s performance on the very factors companies identify as decisive in allocating investment.

How global pharmaceutical investment decisions are made

A wide range of factors shape pharmaceutical investment decisions, but they are often determined by an assessment of whether a country can offer a predictable, supportive environment for developing and launching new medicines.

The ABPI Competitiveness Framework groups these factors into three categories:

1. Baseline requirements – the essential foundations a country must meet before it is even considered: strong IP protection, access to scientific and clinical talent, and a reliable, efficient regulator. If these are weak, a country is ruled out at the outset.

2. Differentiators – the factors that determine where investment goes once baseline conditions are met. These include the stability and predictability of pricing and reimbursement, the health system’s willingness to adopt innovation, and the overall coherence of fiscal and industrial incentives.

3. Contagion risks – areas of pronounced underperformance that can exclude a country entirely from consideration. For example, highly volatile rebate regimes, outdated valuation frameworks, or unpredictable launch and reimbursement pathways – all dynamics that have been prevalent in the UK in recent years (see the preceding chapter) have been decisive deterrents, regardless of scientific strengths.

Taken together, the MIIS results show how rising VPAG rates and long-standing valuation parameters moved the UK further into the contagion risk category at the time the survey was conducted. Future waves of the MIIS will assess whether the new VPAG, NICE and wider pricing and access reforms are sufficient to shift perceptions back towards a more competitive, predictable environment for investment and R&D.

Survey respondent:

“The investments most at risk are in late-stage clinical development, where the greatest financial commitments are required and where the commercial case depends heavily on future pricing and reimbursement certainty. Unlike pre-clinical or early-stage work, late-stage trials require multi-million-pound commitments that are only viable when investors can model future revenues with confidence.”

“In our case, the lack of clarity under the VPAG has already forced us to halt a [multi-million pound] investment into a late-stage clinical programme. The uncertainty around pricing, and whether innovative therapies will be adequately valued in the UK, made it impossible to secure the investment support needed to proceed.”

A large majority of firms reported a direct connection between VPAG levels and their UK operations. Seventy-nine per cent of survey respondents said their company had considered operational or investment reductions in the UK since January 2024, while fewer than one in four said that they had not.

Weighted by employment, the relationship becomes even clearer: firms employing more than 91 per cent of the total UK headcount represented in the survey said they had considered reducing their UK footprint since January 2024.

Survey respondent:

“The non-financial aspects of the UK are fairly attractive for life-sciences. The biggest disincentives about the UK are the affordability controls (i.e. the VPAG and Statutory Scheme) and its willingness to pay (HTA thresholds). Why would you invest in clinical trials in the UK when you know that the UK is not prepared to pay a fair price for innovation?”

2. Lower VPAG rates are associated with stronger employment stability in the UK life sciences sector

Survey results show that VPAG payment levels have become a central factor shaping workforce decisions across the UK life sciences sector. Responding firms report a consistent relationship between the level and predictability of VPAG payments and their ability to sustain UK employment. Lower, more stable rates are associated with stronger workforce confidence, while higher, more variable rates coincide with expectations of contraction. These findings support the government’s decision to stabilise the VPAG by setting a ceiling on the rates of newer medicines in its implementation of the Economic Prosperity Deal.

Survey respondent:

“Despite having a growing pipeline, we have made successive headcount reductions each year since 2022 as a direct result of escalating VPAG rates. There has been a 30 per cent reduction in [our] headcount in the last five years.”

Across the sector, anticipated changes in FTE employment are becoming increasingly clear – particularly among larger companies. Among firms with VPAG-measured sales above £100 million, nine in 21 anticipate reducing their UK headcount in 2026, compared with two in 21 expecting expansion. These firms account for 93 per cent of total FTEs captured in the survey, meaning even incremental workforce changes within this cohort carry significant implications for sector-wide employment.

Similarly, among companies with VPAG-measured sales above £30 million, all but one (27 in 28) said the VPAG was a factor influencing their workforce decisions. At the overall survey level, 83 per cent of firms said VPAG levels are an essential factor in future headcount planning. Weighted by employment, the relationship strengthens: firms employing 95 per cent of all FTEs captured in the survey reported a direct connection between VPAG levels and future UK headcount.

Survey respondent:

“In the short term the commercial rebate is a huge operational factor in our decision making. Do we invest in the market or not and in terms of workforce?”

“In the longer term the unfavourable and uncompetitive pricing environment compared to other EU countries is having a major impact and is making the global organisation ask questions regarding the UK market.”

“While other affiliates are increasing headcount, it is difficult to justify it in UK as pricing is Europe’s lowest and VPAG rebates are crippling.”

Taken together, these results indicate that, at the time of the survey, VPAG levels were a central driver of companies’ UK employment plans, providing an essential baseline against which to assess the impact of the subsequent VPAG and wider pricing and access reforms.

3. The UK’s position in global launch sequences had weakened at the time of the MIIS, with higher VPAG rates expected to delay or reduce future medicines launches

Over the past five years, the UK has experienced a gradual but marked shift in how global companies plan their launches. What was once an early priority market – frequently grouped alongside the US, Germany and other major EU states – has gradually moved down the list. In 2025, that trend has sharpened into a clear and measurable decline. Companies now describe the UK as a “second-wave market”, placed behind multiple countries that once followed its lead.

Across the MIIS sample, nearly two-thirds of responding companies (62 per cent) said the UK’s position had deteriorated over the past five years. Only three companies reported improvement, and only one of these was a large company (above £100m sales). The remainder said the UK had stood still while others moved ahead; an outcome that, in practical terms, amounts to relative decline.

The explanations for this shift are consistent across companies. Respondents emphasised that the value of the UK market had fallen, both because net prices are now among “the lowest in Europe,” and because sustained high VPAG rates were seen as having “significantly eroded the value of individual medicines,” making business cases far more marginal than they were even two years ago. One described the impact bluntly: “giving away up to 35 per cent of our sales immediately”.

At the time of the survey, responding companies also highlighted challenges within NICE’s methods – particularly the rigidity of the baseline cost-effectiveness threshold and the restricted implementation of the severity modifier.

Survey respondent:

“Launch delay due to QALY threshold in the first instance but also compounded by the severity modifier.”

“Taken together, these pressures had reshaped global launch sequencing by the time of the MIIS. Many companies noted that the UK, once “one of the first,” now routinely sits “after the US and EMA,” with “at least six countries … ahead of the UK” in the launch wave.”

Several respondents also pointed to a broader global trend: as boards reprioritise their commercial strategies, markets such as China, Spain, Italy and France increasingly secure earlier slots, while “global teams’ patience with the UK has run dry”.

Survey respondent:

“Launch of this product has been delayed due to global launch sequencing. UK launch has been pushed back due to lower commercial attractiveness when taking into account low net prices and the VPAG.”

Alongside this downward movement in launch order, payment levels under the VPAG appear closely associated with firms’ decisions about the timing and scope of launches in the UK. More than two-thirds of responding companies said that the payment rate levels prevailing at the time of the survey directly influence these decisions.

Sharper decline among the largest companies

The downward shift is even more pronounced among the companies with the greatest footprint in the UK market. Among firms with measured sales above £100 million, more than three-quarters (16 in 21 responding companies) said that the UK’s position in their launch sequence had fallen over the past five years, one said it had improved, and the remainder said it was unchanged. Given that this group represents the majority of UK market activity and launch volume, these results show a consistent pattern of decline among the companies most active in launching new medicines in the UK.

Survey respondent:

“Low thresholds make pricing challenging anyway, but commercial flexibility was also required given low cost-effectiveness threshold. Historically, this made the business case request to the global organisation marginal, but once rates increased in 2025 approvers began to question the commercial viability of launch.”

The consequences of the UK falling down the launch sequence

The UK’s declining position in global launch sequencing has had clear and measurable effects on patient access and market behaviour, with 46 medicines experiencing a negative launch impact.

Contextualising MIIS with other macro evidence

The MIIS launch findings align with wider macro access indicators for medicines in the UK, providing additional insight into the drivers behind these trends.

- NICE TA/HST outcomes (2024/25) suggest a higher non-positive rate than MIIS alone captures: combining not-recommended (8%) and terminated appraisals (17%) implies ~25% of topics did not result in a positive outcome.

- NICE–ABPI termination interviews across 49 indications highlight expectations of unfavourable NICE outcomes and commercial viability constraints — consistent with MIIS evidence on the combined impact of VPAG rates and NICE thresholds.21

- EFPIA’s Patients W.A.I.T. Indicator shows that 35% of centrally authorised medicines (2020–23) are not available in England, reinforcing constrained access patterns seen in company-reported launch decisions.22

The MIIS dataset identifies 18 medicines, including new indications, whose launches have been delayed in the UK while progressing elsewhere in Europe. Companies consistently attributed these delays to the interaction of NICE cost-effectiveness thresholds, the implementation of the severity modifier, and the impact of sustained high VPAG rates on viable pricing. One firm delaying an ovarian cancer therapy noted that launch had been halted due to the threshold. In ophthalmology and neurology, companies highlighted that the required UK net prices afford “no room for flexibility,” leading to successive postponements.

At the same time, companies reported being limited to private-only launches, with 17 medicines, including new indications, proceeding through this route. This reflects circumstances in which the UK price required for NHS reimbursement is already significantly below international comparators and, once the VPAG is applied, can fall below the cost of goods. In oncology, this has resulted in advanced therapy medicinal products – which offer the possibility of a functional cure – being made available privately, but not through the NHS – a bad outcome for health equality and inclusion. In rare diseases, companies report that NICE-acceptable prices are “orders of magnitude” lower than elsewhere, making formal submission unsustainable.

Together, these developments show that falling down the global launch sequence does not simply push the UK further down the queue. In some cases it can result in no NHS access at all; a pattern that, left unchecked, risks deepening inequalities and weakening the UK’s attractiveness for future innovation.

The MIIS does not replace aggregated data sets on access to medicines, including the appraisal outcome data published by NICE, but the findings are supplementary and provide additional granularity on why company decisions are made and how patients might be affected.

The data can therefore support in providing an essential baseline against which to assess whether the proposed reforms to the commercial operating environment for pharmaceuticals can reverse this trajectory over time.

Conclusion

The UK’s life sciences sector has historically been one of the nation’s defining strengths. Across the UK, the industry supports more than 125,000 high-skilled jobs, is responsible for £9.3bn of R&D spending – £1 in every £6 by the private sector and contributes more than £17 billion in direct gross value added annually to the economy; its products also play a vital role in the care of many patients, and support the productivity and efficiency of the sector.23, 24, 25

In December, the government announced several significant measures to implement the Economic Prosperity Deal, increasing the prices of new medicines through changes to NICE methods and capping the VPAG newer medicines rate so that it is no higher than 15 per cent in future years. Alongside this, the government committed to long-term spending targets so that spending on newer medicines rises from 0.3 per cent to 0.6 per cent of GDP – with a growing share of health spend allocated to all medicines from 10 per cent to 12 per cent – over the next 10 years. To implement these measures, the government is also preparing to engage industry on the design of a future voluntary scheme.26 This deal is an important first step in supporting patients so they can continue to access innovative medicines, and halt the further exodus of life sciences investments recently seen in the UK.

As this report sets out, this comes at a crucial time for the sector. The MIIS is a snapshot of the period immediately preceding the deal announcement and captures one of the most challenging periods the industry has faced. For more than a decade, pressure has been mounting on the UK’s leadership of the sector to be able to prioritise medicine launches when the parameters NICE has been set to work within have remained frozen. At the same time, VPAG payment rates had increased from an average of 6.9 per cent in the first capped scheme to 23 per cent for newer medicines in 2025 and 10-30 per cent for older medicines. This reduces the proportion of company revenues available for operations or further investment; at times, surges in the rate have forced companies to disinvest or consider withdrawing from the market. Withdrawals are even more notable as medicines become older and might be offering increasing discounts to the NHS as competition increases.

Companies have long voiced concerns about the growing challenges of the UK environment, and the evidence in this report shows that in 2025, companies have been acting on them. The ABPI’s ‘Opportunity Unlocked’ report, published in early 2025, highlighted that rising VPAG payment rates and growing volatility risked diverting more than £2.6 billion of planned R&D away from the UK.27 In the months since, these identified risks have translated into action: companies have cancelled or paused around £2 billion of investment.28

Further, the MIIS captures several critical areas of life sciences activity that will be important to track following the implementation of commitments made to improve the operating environment for pharmaceuticals in the UK:

- Investment – more than three-quarters of responding companies reported that their firms had considered operational or investment reductions in the UK since January 2024, with a wide variety of investment types impacted.

- Workforce – four in five responding firms said that VPAG levels were a key factor in future headcount planning in the UK.

- Priority launch market – two-thirds of firms have delayed or deprioritised at least one UK launch.

- Delayed medicines launches – 18 products spanning more than nine disease areas, from oncology and cardiovascular to rare and ultra-rare diseases, with all these products set to be available in the EU, thereby reflecting particular challenges in the UK commercial environment.

- Private-only medicines launches – continuing with the trends outlined in the ‘Opportunity Unlocked’ report, companies report a growing shift towards launching products exclusively on the private market. High payment rates and persistent challenges securing NHS reimbursement have led firms to identify 17 medicines for private-only launch.

- Cancelled medicines launches – seven products were not launched in the UK at all, with companies concluding that prices required to be considered cost-effective by NICE and VPAG rebate rates render the UK market commercially unviable. As a result, medicines available elsewhere in Europe are not being brought to UK patients.

Taken together, these findings underline the importance of implementing the commitments and evidencing tangible successes in restoring confidence in the UK – both as a launch market and an investment destination.

The opportunity to restore confidence

Companies were clear in their responses about the importance of both VPAG rates and NICE thresholds as factors driving their activity in the UK. That the government has begun to address these issues is a good sign. Stability in VPAG payment rates and a more permissive approach to valuing medicines is an important step towards providing the predictability global boards need to prioritise the UK once again.

However, there remains significant uncertainty for companies providing medicines in the UK, both for new launches and existing portfolios – the most important element of this is the most-favoured-nation pricing policy, which aims to set prices for US buyers by referencing prices paid in a basket of other countries, which includes the UK. The impacts of this on many markets could be significant; more so for countries like the UK, which has spent more than a decade suppressing net prices.

Taken together, this report offers hope: it recognises the deal as a positive step by the government towards better access for patients and a more competitive UK environment, but also underlines that the opportunity it creates remains fragile and will depend on consistent implementation, coherent pricing and access policy and delivery of continued improvements beyond those announced in December last year.

Methodology

The evidence base for this report draws on a mixed-method research programme undertaken by Global Counsel (GC) in partnership with the ABPI.

The primary source for the analysis presented is the 2025 ABPI Medicines and Investment Survey, conducted in September–October 2025 and completed by 42 UK pharmaceutical companies, both within and outside the ABPI’s membership.

The survey was designed to build a repeatable, longitudinal evidence base on how UK policy conditions – including sustained high VPAG payment rates – are influencing company behaviour and investment, workforce, and medicines launch prioritisation decisions.

This iteration consolidated previous ABPI surveys on older and newer medicines into a single questionnaire, capturing both leading indicators (such as investment intentions and pipeline launches at risk) and lagging outcomes (such as realised launches, headcount changes, and clinical activity). Companies were also invited to provide qualitative commentary explaining how UK pricing and access policies, including the VPAG, are shaping their business planning and future footprint. These inputs have shaped the drafting of this report, alongside GC-facilitated discussions with the ABPI’s commercial board-sponsored group.

Quantitative results from these responses were complemented by qualitative coding of open-text responses to identify recurring themes around competitiveness, market prioritisation, and policy impact.

Results were subsequently discussed with the ABPI commercial board-sponsored group to stress-test emerging insights and align the overarching narrative with broader developments in the UK external environment vis-à-vis the UK government’s approach to medicines pricing during the period in which this report was drafted.

Endnotes

- ABPI, ‘Creating the conditions for investment and growth’, 10 September 2025.

- Two medicines were outside of the HTA remit.

- ABPI, ‘Opportunity unlocked: how UK medicine spend policy can free the life sciences sector to drive growth’, 3 June 2025.

- Defined as firms with reported measured sales of over £30 million. Excludes don’t knows.

- ABPI, ‘Opportunity unlocked: how UK medicine spend policy can free the life sciences sector to drive growth’, 3 June 2025.

- ABPI, ‘Creating the conditions for investment and growth’, 10 September 2025.

- ABPI analysis of outturn NHS Budget (RDEL) across the four nations, adjusted for inflation (GDP inflator).

- IQVIA Institute, ‘Drug expenditure dynamics 2000–2022’, 21 October 2025.

- ABPI analysis of outturn NHS Budget (RDEL) across the four nations, adjusted for inflation (GDP inflator).

- ABPI analysis of out turn NHS budgets across the four nations and allowable growth rates between 2015 PPRS and 2024 VPAG, with December deflator applied, 2026.

- Charles River Associates, ‘Benchmarking the UK’s cost-effectiveness threshold: findings from international comparison’.

- Charles River Associates, ‘Benchmarking the UK’s cost-effectiveness threshold: findings from international comparison’.

- Ibid.

- UK Parliament, ‘Science, Innovation and Technology Committee: life sciences investment, session 2’, 16 September 2025.

- Ibid.

- Financial Times, ‘Merck slams UK as it scraps £1bn London drug research centre’, accessed November 2025.

- BBC, ‘AstraZeneca pauses £200m Cambridge investment’, accessed November 2025.

- UK Parliament, ‘Science, Innovation and Technology Committee: life sciences investment, session 2’, 16 September 2025.

- Ibid.

- ABPI, ‘Creating the conditions for investment and growth’, 10 September 2025.

- Medicines data: NICE approvals and availability in England.

- VPAG Operational Review Metrics Pack, slide 7.

- Office for National Statistics, ‘Regional gross value added (balanced) by industry’, accessed November 2025.

- Office for National Statistics, ‘Business enterprise research and development, UK, 2023’, accessed November 2025.

- Office for National Statistics, ‘Regional gross value added (balanced) by industry’, accessed November 2025.

- UK government, ‘Landmark UK-US pharmaceuticals deal to safeguard medicines access and drive vital investment for UK patients and businesses’, 1 December 2025.

- ABPI, ‘Opportunity unlocked: how UK medicine spend policy can free the life sciences sector to drive growth’, 3 June 2025.

- The Guardian, ‘Big pharma firms ramping up UK investment amid Trump-era shifts’.

-

PublisherABPI

-

Last modified26 January 2026

-

Last reviewed26 January 2026